More "Stonewalling" about $6 Million Legal Fees for Dave Basi and Bob Virk

|

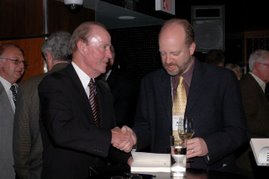

| Lawyer Roger McConchie and BC Conservative MLA John van Dongen outside BC Supreme Court hearing into Basi-Virk indemnity legal fees payment - Bill Tieleman photo |

Auditor general, van Dongen battle lawyers to get to

bottom of legal bill payment by BC tax payers

Tuesday September 18,

2012

By Bill Tieleman

"Stonewalling is

a good term to use to describe this situation overall and in this case."

- John van Dongen, BC

Conservative MLA

How

did two former ministerial aides charged with breach of trust and fraud get

their $6 million legal fees paid by the B.C. Liberal government despite

pleading guilty in the B.C. Legislature

Raid case?

We

may never know, despite B.C.'s independent auditor general John Doyle

attempting to find out through a B.C. Supreme Court application heard for five

days last week.

And

the hallmark of the lengthy B.C. Legislature Raid case -- delay -- emerged

again, with Doyle's application first put off from June to September and now

recessing until early December for final arguments, meaning Chief Justice

Robert Bauman is unlikely to make a ruling until 2013.

The

issue arises from one of the province's biggest political scandals ever -- with

B.C. Liberal government political aides Dave Basi and Bob Virk charged with

leaking confidential documents in the $1 billion privatization sale of B.C.

Rail in 2003 to lobbyists for a losing bidder in exchange for money and other benefits.

Government

employees facing charges can have their legal defence bills covered under a

process called indemnification -- but only if they are acquitted.

But

Basi and Virk made a sudden surprise guilty plea in Oct. 2010 ending their

trial after hearing testimony from just two of an expected 40 witnesses --

including former and current top politicians and staff, possibly even Premier

Christy Clark and former premier Gordon Campbell.

Basi

and Virk had strongly protested their innocence since the case exploded with an

unprecedented police raid on the B.C. Legislature in Dec. 2003 to gather

evidence against the two men.

Doyle's

efforts to obtain the controversial Basi-Virk legal billings and those of about

100 other government officials whose costs were indemnified since 1999 are

being strongly opposed in court, primarily on the basis that solicitor-client

privilege blocks his access to the billings of lawyers.

Doyle's

legislative authority to conduct an audit and make recommendations to

government is also being questioned.

'An

incredible effort to avoid accountability'

Outside

a courtroom where government is funding up to eight lawyers to argue various

sides of the case, John van Dongen, a former B.C. Liberal solicitor general who

quit the party in March in part because of Basi-Virk, was "very

frustrated."

"There's

a fair question whether this issue should be in this courtroom at all and

whether it's properly motivated," van Dongen said in an exclusive

interview. "There's an incredible effort to avoid accountability and

transparency to taxpayers -- there's a problem here."

"Disclosure

has been avoided and covered up," said van Dongen, who was given

intervener status by Bauman on the grounds that his past position could add

information useful to the court.

While

van Dongen was a B.C. Liberal cabinet minister and insider for many years, he

says he found out about the $6 million payment of legal fees the same day as

the public did from then-B.C. attorney-general Mike de Jong, now finance

minister.

Veteran

lawyer Roger McConchie was retained by van Dongen at his own personal expense

to make submissions supporting the auditor-general's application and attend the

entire hearing, as did the Abbotsford-South MLA.

Perhaps

ironically given the importance of the principles involved, throughout the

whole hearing there were always more lawyers in the courtroom than media and

observers combined.

In

court, McConchie made a powerful argument that denying the auditor-general

confidential access to legal billings in indemnification cases was wrong.

"Where

the public interest cries out for investigation and audit, the court should be

able to permit access to privileged information," McConchie told Bauman.

And

McConchie said the "auditor-general plays an extremely important

role" in ensuring that government spending is accountable to taxpayers.

"An

audit has a sobering effect on conduct," McConchie said. "The

salutary deterrent effect is that a possible audit by the auditor-general can

have on ministries owes its effect to the possibility of a wide-ranging,

unrestricted audit."

Auditor

general's plea for access

McConchie's

50-page submission and arguments echoed those of the auditor-general's legal

counsel Louis Zivot, who filed a 111-page submission with hundreds of

references to case law and legislative authorities to back the application.

"It

was intended by the legislation that the Auditor general have full

access," Zivot told Bauman. "The legislation could have been drafted

to exclude legal expenditures."

"If

we have to negotiate with the attorney general as to what we can have and how

we can have it, it will impede the auditor general," Zivot said.

"It

is absolutely necessary that the Auditor general have access to all these

documents," he said. "While a good deal of focus is on Mr. Basi and

Mr. Virk... they are only two of the hundreds of recipients of

indemnities."

The

records that have been given to the auditor general have been severely severed

or redacted, effectively rendering many of them useless, Zivot said.

"Some

pages are virtually black -- you can't tell who conversations were with --

these are insufficient for auditing accounts," Zivot said. On

the lectern in front of Zivot observers could clearly see a document with

blacked out pages.

In

concluding, Zivot warned that a decision against Doyle would not only

negatively impact the B.C. auditor general's powers but those of other

provinces as well, who have very similar legislative authority.

"Essentially

this is a very important matter for the auditor general of British Columbia but

also for other auditor generals," Zivot said. "A finding that the

auditor general does not have these powers would have an adverse effect on the

[B.C.] auditor general, other auditors general and auditors."

The

other side

But

strong arguments against the auditor general's application for these files were

also heard in court.

While

the government has not taken a position for or against Doyle's application, an

amicus curiae or "friend of the court" was appointed by the court to

oppose the auditor general's application with all relevant arguments to protect

solicitor-client privilege.

Not

only were lengthy arguments made in an 88-page submission strongly fighting

Doyle's position but lawyer Michael Frey [pronounced Fry] previously opposed

van Dongen's application for intervenor status, saying the former veteran

cabinet minister had nothing to add to the case.

When

it came to the auditor general's application, Frey was completely dismissive of

its merits.

"The

Amicus's first and foremost submission to this court is that, as a matter of

statutory interpretation and law, the petitioner [Doyle] has no power to compel

the abrogation of solicitor client privilege. His general production power in

the [auditor general] act does not authorize the infringement of

privilege," Frey wrote.

"Further,

the amicus submits the petitioner has also significantly overreached in

claiming that the standards justify an interpretation of the act that empowers

him to compel abrogation of solicitor client privilege, or an absolute

necessity for compelled interference with the privilege on any basis in

connection with audit work," he continued.

Frey

noted in court that Doyle's office has received partial records of

indemnification legal billings that have been redacted -- or blacked out to

remove some details -- and could conduct his audit with those.

Justice

Bauman intervened to ask for clarification at that point.

"Is

your argument that what he [the auditor general] can get through redacted

material... ought to be plenty enough?" Bauman asked.

"Yes,"

Frey quickly responded.

Mysterious

Sandra Harper

Basi

and Virk are also opposing the auditor general -- at least in part. They have

given a partial waiver on access to those documents possessed by government --

but not the files of two lawyers retained to independently review the legal

bills of Michael Bolton, lawyer for Basi and Kevin McCullough, lawyer for Virk.

And

as always with the B.C. Legislature raid case, efforts to find out what

happened invariably uncover yet more mysteries.

One

of the lawyers attending the full five-day hearing was Sandra Harper, one of

the independent reviewers of Basi and Virk's legal costs.

Harper

took the stand briefly to explain her position: that she declined to provide

her files to the auditor general when he requested them, saying that while she

did not object, Virk did, and so Doyle should seek a court order for her to

produce them.

But

things took a strange turn in her testimony on Sept. 12.

"I

acted as the independent reviewer of counsel for the accused, Mr. Basi and Mr.

Virk, until Sept. 2010, when I resigned," she told Bauman.

What?

The only independent reviewer of the $6 million in legal fees for the accused

for five years quits just weeks before the actual trial starts in Oct. 2010?

Naturally,

I wanted to know why, and approached Harper as she left court on a break

Friday.

Tieleman:

"Bill Tieleman, with 24 hours newspaper and The Tyee, Ms. Harper -- may I

ask you one simple question?"

Harper:

"No."

Tieleman:

"But don't you even want to know the question?"

Harper:

"I won't be talking to the media. You may find out the answers through

others at the court."

And

with that she was gone, leaving the puzzle additionally intriguing.

But

wait, there's more.

Harper

also publicly opposed van Dongen's application for intervenor status when it

was made in May.

"It's

so politically motivated and so off topic that I'm very concerned that Mr. van

Dongen's real message is not inside court but outside court and there's a very

real concern of the application becoming politicized," she said then.

"The Basi-Virk matter has been political enough."

That

view didn't hold sway with Bauman, who granted van Dongen's request,

saying: "I am satisfied that a responsible intervention will be

made."

But

it's hard for this case to avoid being "political" when the

co-accused were both senior B.C. Liberal ministerial assistants who leaked

confidential government material not only to lobbyists Erik Bornmann and Brian

Kieran -- who were never charged and were slated to become key Crown witnesses

-- but also to Bruce Clark, the premier's own brother, who also was never

charged with any offence.

So

why is Sandra Harper not willing to tell the public why she quit as the

reviewer of Basi and Virk’s legal bills?

And

why did she openly oppose van Dongen's application for intervenor status?

Hard

to know when Harper won't even hear questions, let alone answer them.

But

there's no record of Harper making political donations to any party on the

Elections BC financial reporting website.

Fog

has yet to lift

And

so the mysteries continue nearly nine years after the Basi-Virk/B.C.

Legislature raid case first exploded into public view.

Since

that time the overall costs to the public have topped $18 million, including

prosecution and RCMP expenditures as well as Basi and Virk's legal bills.

Overall,

it's clear that win or lose, the auditor general's application will not be able

to answer the much larger questions of what happened when the government sold

the publicly-owned B.C. Rail that it has promised in 2001 to keep.

That's

why it's worth continuing to call for a public inquiry, which has been

supported by the B.C. New Democrats, the B.C. Conservatives and the B.C. Green

Party.

But until

and unless that inquiry takes place, there are too many mysteries and not

enough clues.

.